A cornerstone of DC Pride has always been the concept of reclamation. From the very onset of the medium, queer comics and characters have always existed. It was a closed-minded, puritanical crusade in the mid-twentieth century which drove the most creative and diverse voices in comics into the dark, allowing a largely male heteronormative attitude to drive the mainstream for decades. It’s only in the past thirty years that mainstream comics have been able to openly express queerness again, ever so slowly.

There’s a lot of damage that has to be undone. There’s a lot to take back, and a lot to correct, step by hard-won step, as America widens its point of view. In her journey from sultry man-crazy femme fatale to awesome sapphic eco-warrior, no character encompasses this journey for women and the queer community quite like Poison Ivy.

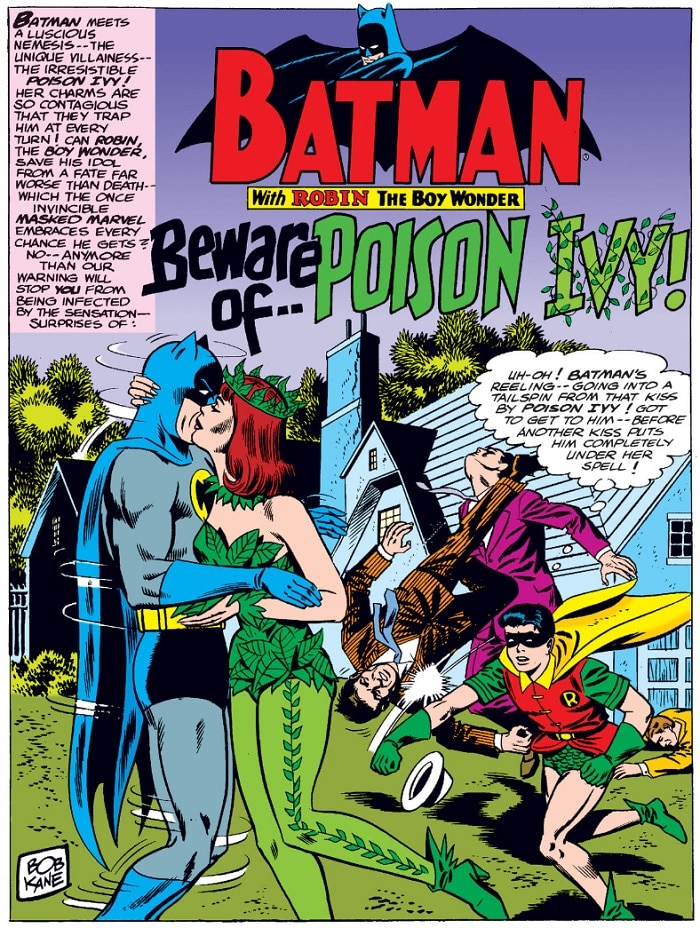

According to editor Carmine Infantino, the original purpose of Poison Ivy was never actually realized. The surprise popularity of Julie Newmar’s Catwoman in the first season of the Batman television show had executives rethinking the decision to largely shelve the character twelve years prior for being too sexually suggestive. In fact, the order came to incorporate more female characters to populate Gotham City who could be incorporated into the new TV sensation. One of these, Batgirl, would successfully make the jump in Batman’s third season and change the dynamic of the Bat-Family forever. The other was Poison Ivy. Sadly, the Batman TV show would be canceled before Poison Ivy could be translated into live action—we’d have to wait another thirty years for that.

From her introduction on through the Pre-Crisis era, Poison Ivy was written in the way women all too often were through all forms of media at the time—in competition with other women, vying for the affection of a man. The first Poison Ivy story, Batman #181’s “Beware of Poison Ivy,” depicts her as a villain on the rise with only one goal: to become the #1 most wanted female villain in Gotham City. A bit of metacommentary on how she was created in Catwoman’s shadow, perhaps, though Catwoman herself never appears or is even mentioned in this story. Poison Ivy changes course the first time she encounters Batman in this quest to conquer Gotham’s gendered crime charts with her plant-themed crimes. Ravished by the mere presence of the Caped Crusader, Ivy determines that she will make Batman love her as she has become so quickly enamored with him.

This initial incarnation of Poison Ivy reached its peak in the 1997 film Batman and Robin, where an iconic Uma Thurman delivered a camp performance worthy of the Adam West series writ large. But by then, a newer perspective on Poison Ivy was already on the rise.

As much as Poison Ivy’s creation can be attributed to the Batman show, Carmine Infantino, Sheldon Moldoff and Robert Kanigher, Pamela Isley as we know her today was truly born between 1988 and 1992 from the work of Neil Gaiman, Dave McKean, Bruce Timm and Paul Dini.

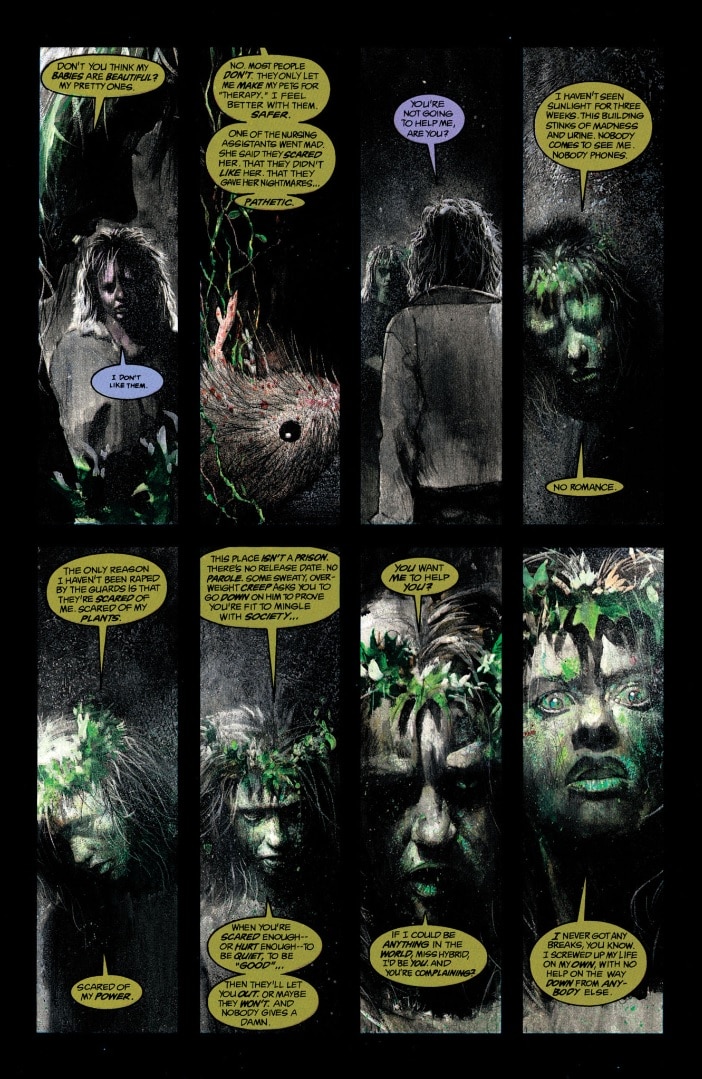

A year before Grant Morrison would offer their own reinterpretation of Arkham Asylum in A Serious House on Serious Earth, Gaiman and McKean took their own heroine, Black Orchid, into the recesses of Arkham to explore the dire circumstances which always result in escape and recidivism therein. Their plant-based hero meets her counterpart, Poison Ivy, with a closer affinity to plant life than ever before and the agony of a woman abused by the patriarchy all her life. Gaiman would elaborate on this moving scene with Ivy from Black Orchid in Secret Origins #36, allowing Ivy to truly tell her own story for the first time, revealing the abuse at the hands of her professor which led her down her dark path.

Poison Ivy had always used plants in her crimes, most notably as the components of her deadly lipstick. But it was Bruce Timm and Paul Dini’s Batman: The Animated Series that made plants more than merely her weapon of choice. In the early episode “Pretty Poison,” Ivy takes radical action to prevent a new prison being built on the island home of some rare plant life, establishing her new modus operandi not as a competitor to other women, or hopeful for the heart of a man, but as a champion of the environment in a short-sighted and selfish world. A later episode, “Harley and Ivy,” presented Poison Ivy with her partner in crime, enriching both characters as one escaped the Joker’s shadow and the other escaped her perception of other women as rivals. Over time, that Thelma and Louise partnership would develop into much more.

The face of Gotham City would change forever in the epic, year-long “No Man’s Land” event of 2000, redefining characters along with the city itself. A new Batgirl made her debut. Harley Quinn arrived in comics continuity. And in Robinson Park, Pamela Isley was protecting children displaced from the city-wide chaos within the greenest part of the city, presenting an Ivy capable of sympathy and heroism. The femme fatale days were well and truly over. In this period, even Ivy’s past crimes are recontextualized as we learn the riches she’s gained have gone towards rewilding the rainforests. From here on out, Ivy’s core motivation would be caring. (Often too aggressively, one could argue.)

Ivy’s friendship circle would expand in 2009’s Gotham City Sirens, incorporating Catwoman into her crusades. And throughout their developing partnership, more readers would continue to pick up on the subtext of Harley and Ivy’s relationship—there was clearly something else going on there. Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy were two women often reduced to cartoon caricatures in desperate need of sympathy and human connection, which, when found, was usually in each other. Playful flirtations developed between them over time and into Jimmy Palmiotti and Amanda Conner’s Harley Quinn comics, ultimately culminating in season two of the animated Harley Quinn.

As we chronicled in great detail for last year’s DC Pride, that was the point Harley and Ivy’s relationship really took off. From then on, the queens of Gotham could own their relationship in public—just in time for Poison Ivy to land her own ongoing series.

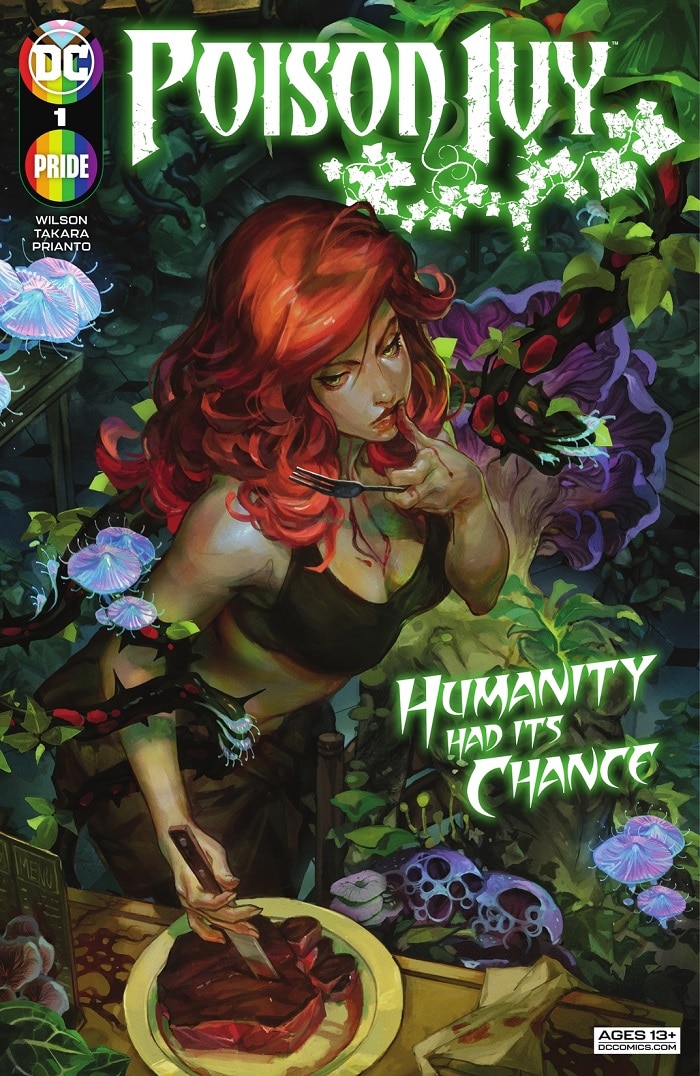

Now running over twenty issues and counting, G. Willow Wilson’s Poison Ivy richly draws on everything that’s made the character so compelling since she could first tell her own story. Shades of Black Orchid, “No Man’s Land” and Batman: The Animated Series run through the character as she declares in the series’ bold tagline, “HUMANITY HAD ITS CHANCE.”

Is Poison Ivy a hero? No. She was never meant to be. But she is, like Batman himself, a crusader. She doesn’t exist to define herself by rivalry, or even by love, though Harley nurtures her like rich soil. Robert Kanigher and Sheldon Moldoff might not have known Ivy’s relationship to plants back in the 1960s had planted the seeds for her to become the vengeful champion of the Green. But they’ve been sprouting since 1992. And now? Now, they flower.

Alex Jaffe is the author of our monthly "Ask the Question" column and writes about TV, movies, comics and superhero history for DC.com. Follow him on Bluesky at @AlexJaffe and find him in the DC Community as HubCityQuestion.

NOTE: The views and opinions expressed in this feature are solely those of Alex Jaffe and do not necessarily reflect those of DC or Warner Bros. Discovery, nor should they be read as confirmation or denial of future DC plans.